Long COVID: An overview

长新冠:概述

A.V. Raveendran a b, Rajeev Jayadevan c, S. Sashidharan d

Long COVID: An overview

长新冠:概述

Available online 20 April 2021 A.V. Raveendran a b, Rajeev Jayadevan c, S. Sashidharan d

疲劳、咳嗽、胸闷、呼吸困难、心悸、肌痛和难以集中注意力是长期 COVID 中报告的症状。它可能与器官损伤、病毒后综合症、重症监护后综合症等有关。

1 .介绍

SARS-CoV-2 感染 (COVID-19) 是一种主要的流行病,在全球范围内导致了大量的死亡率和发病率。在受影响的个体中,约 80% 患有轻度至中度疾病,而在患有严重疾病的个体中,5% 发展为危重症 [ 1 ]。一些从 COVID-19 中康复的人会出现持续数周或数月的持续症状或新症状;这被称为“long COVID”、“Long Haulers”或“Post COVID syndrome”。

1.1 急性冠状病毒

感染 SARS-CoV-2 病毒的人通常会在接触后 4-5 天出现症状。急性 COVID 症状包括发烧、喉咙痛、咳嗽、肌肉或身体疼痛、味觉或嗅觉丧失以及腹泻。来自英格兰、威尔士和苏格兰的一项研究确定了急性疾病期间的三组症状 [ 2 ]。他们是

• 呼吸道症状群:伴有咳嗽、咳痰、呼吸急促和发热;

• 肌肉骨骼症状群:伴有肌痛、关节痛、头痛和疲劳

• 肠道症状群:腹痛、呕吐和腹泻

• COVID 症状研究小组确定了六组症状 [ 3 ]。他们是:

• 没有发烧的“流感样”——头痛、嗅觉丧失、肌肉痛、咳嗽、喉咙痛、胸痛,没有发烧

• “流感样”伴有发烧——头痛、嗅觉丧失、咳嗽、喉咙痛、声音嘶哑、发烧、食欲不振

• 胃肠道——头痛、嗅觉丧失、食欲不振、腹泻、喉咙痛、胸痛、无咳嗽

• 严重一级,疲劳——头痛、嗅觉丧失、咳嗽、发烧、声音嘶哑、胸痛、疲劳

• 严重二级,精神错乱——头痛、嗅觉丧失、食欲不振、咳嗽、发烧、声音嘶哑、喉咙痛、胸痛、疲劳、精神错乱、肌肉痛

• 严重三级,腹部和呼吸——头痛、嗅觉丧失、食欲不振、咳嗽、发烧、声音嘶哑、喉咙痛、胸痛、疲劳、意识模糊、肌肉疼痛、呼吸急促、腹泻、腹痛

从轻度 SARS-CoV-2 感染中恢复通常发生在轻度疾病症状出现后 7-10 天内;严重/危重疾病可能需要 3-6 周 [ 4 ]。然而,对从 COVID-19 中康复的患者的持续随访表明,在相当大比例的人中,一种或多种症状持续存在,甚至在 COVID-19 后数周或数月。

1.2 “长COVID”

Perego 首次在社交媒体上使用长期 COVID一词来表示在最初感染 SARS-CoV-2 后数周或数月症状持续存在,Watson 和 Yong 使用术语“长途运输者”[[5],[ 6 ] , [7] ].

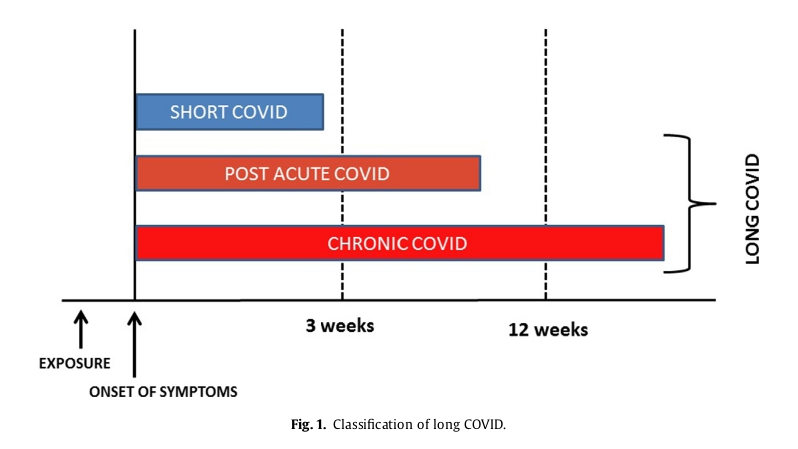

“长期 COVID”是一个术语,用于描述各种症状的存在,甚至在获得 SARS-CoV-2 感染后数周或数月,无论病毒状态如何 [8 ]。它也被称为“后 COVID 综合症”。它可以是持续性的,也可以是自然复发和缓解的 [ 9 ]。急性 COVID 的一种或多种症状可能持续存在,或出现新症状。大多数 COVID 后综合症患者的 PCR 呈阴性,表明微生物已恢复。换句话说,后 COVID 综合症是微生物恢复和临床恢复之间的时间差 [ 10]. 大多数患有长期 COVID 的人表现出生化和放射学恢复。根据症状的持续时间,COVID 后或长期 COVID 可分为两个阶段——症状超过 3 周但少于 12 周的急性 COVID 后和症状超过 12 周的慢性 COVID [11 ]。(图1 )。

因此,在感染 SARS-CoV-2 的人群中,即使在预期的临床恢复期之后,仍存在一种或多种症状(持续或复发和缓解;急性 COVID 的新症状或相同症状)的定义,无论其潜在机制如何作为 COVID 后综合征或 Long COVID。

长 COVID 的诊断存在几个挑战。临床康复所需的时间因疾病的严重程度而异;而相关的并发症使得难以确定诊断的截止时间。很大一部分 SARS-CoV-2 感染者没有症状,许多人不会接受任何测试来确认 SARS-CoV-2 感染。如果这些人随后出现多种症状,那么在没有 SARS-CoV-2 感染的先前证据的情况下做出长期 COVID 的诊断是具有挑战性的。不同国家/地区的检测政策各不相同,在大流行期间,通常的做法是根据症状进行临床诊断,而无需进行任何确认性检测。因此,那些从未检查过 COVID 的人的症状持续存在是一个挑战 [12 ]。同样,那些 COVID 检查呈阴性的人的残留症状(假阴性,因为检测可能在病程中过早或过晚进行)也可能增加诊断困境 [ 13 ]。对感染的抗体反应也各不相同,大约 20% 没有血清转化。抗体水平可能会随着时间的推移而降低,这对近期 SARS-CoV-2 感染的回顾性诊断提出了挑战[ 14、15 ]。

1.3 “Long COVID”——真实世界场景

来自意大利的一份报告发现,即使在 60 天时,87% 的康复和出院患者仍表现出至少一种症状 [ 16 ]。其中 32% 的人有一种或两种症状,而 55% 的人有三种或更多症状。这些患者未见发热或急性疾病特征。常见的问题是疲劳(53.1%)、生活质量恶化(44.1%)、呼吸困难(43.4%)、关节痛(27.3%)和胸痛(21.7%)。报告的其他症状包括咳嗽、皮疹、心悸、头痛、腹泻和“针刺感”。除了焦虑、抑郁和创伤后应激障碍等心理健康问题外,患者还报告无法进行日常活动。

另一项研究发现,出院的 COVID-19 患者即使在 3 个月时也会出现呼吸困难和过度疲劳 [ 17 ]。

在门诊接受 COVID-19 治疗的患者中,残留症状的患病率约为 35%,但在住院患者队列中约为 87% [ 16、18 ]。

根据一项调查 [18 ] ,在 COVID 呈阳性后 14-21 天未能重返工作岗位的人数比例为 35% 。它在较大年龄组(18-34 岁 26%,35-49 岁 32%,50 岁及以上 47%)和有合并症的人群(28% 没有或只有一种合并症)中更为常见, 46% 有两种和 57% 有三种或更多合并症)。肥胖 (BMI>30) 和存在精神疾病(焦虑症、抑郁症、创伤后应激障碍、偏执狂、强迫症和精神分裂症)与术后 14-21 天不重返工作的几率高出两倍以上有关一个积极的结果 [ 18]. 感染急性期出现的发烧和发冷分别在 97% 和 96% 的个体中消失。但在采访中,43%、35% 和 29% 的患者咳嗽、疲劳和呼吸急促没有得到解决。味觉丧失和嗅觉丧失需要更长的时间才能解决(8 天)。根据最近的一项荟萃分析,Long COVID-19 的 5 种最常见表现是疲劳 (58%)、头痛 (44%)、注意力障碍 (27%)、脱发 (25%)、呼吸困难 (24%) [ 19 ].

在长期使用呼吸机的重症监护病房患者中,残留症状很常见。然而,患有轻度疾病的 COVID 患者也报告没有恢复到 COVID 前的健康状态,这有效地质疑了“轻度”疾病的术语。

1.4 长期 COVID 的危险因素

对 COVID 康复患者的随访确定了一些通常与长 COVID 发展相关的因素。与男性相比,女性患长 COVID 的风险是男性的两倍 [ 9 ]。年龄增长也是一个危险因素,研究发现长 COVID 患者比没有长 COVID 的患者大四岁左右 [ 9 ]。在疾病的急性期出现超过 5 种症状与发展为长期 COVID 的风险增加有关 [ 20 ]。与长期 COVID 最常见的症状包括疲劳、头痛、呼吸困难、声音嘶哑和肌痛 [ 20]. 合并症的存在也会增加患上 COVID 后综合症的风险。即使是那些在初次就诊时症状较轻的人,也被发现会发展为长期 COVID。

1.5 “长 COVID”的病理生理学

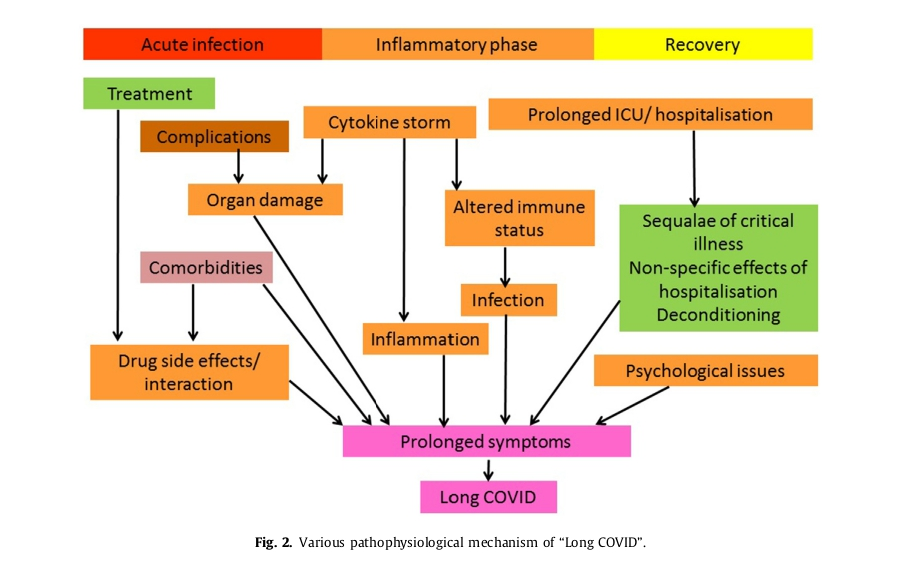

必须确定症状持续存在背后的确切机制。症状持续存在的原因可能是器官损伤的后遗症、不同程度的损伤(器官损伤)和每个器官系统恢复所需的不同时间、持续的慢性炎症(恢复期)或免疫反应/自身抗体的产生,病毒在体内的罕见持久性、住院的非特异性影响、危重病后遗症、重症监护后综合症、与电晕感染相关的并发症或与合并症相关的并发症或所用药物的不良反应 [21、22]。(图1 )2)持续感染可因持续病毒血症在免疫力改变、再次感染或复发的人群中 [ [23]、[24]、[25]。失调、创伤后应激等心理问题也会导致症状 [ [26]、[27]、[28] ]。COVID-19 的社会和经济影响也导致了包括心理问题在内的后 COVID 问题。从公共卫生的角度来看,将残留症状与再次感染区分开来很重要。持续升高的炎症标志物指向慢性持续性炎症。请记住,在任何患者中,多种机制都可能导致长期 COVID 症状。

1.6 “Long COVID”中的常见症状

“长期 COVID”患者的常见症状是极度疲劳、呼吸困难、咳嗽、胸痛、心悸、头痛、关节痛、肌痛和无力、失眠、针刺感、腹泻、皮疹或脱发、平衡和步态受损、神经认知包括记忆力和注意力问题以及生活质量恶化在内的问题。患有“长期 COVID”的人可能会出现一种或多种症状。

研究人员确定了长期 COVID 患者的两种主要症状模式:它们是 1) 疲劳、头痛和上呼吸道不适(呼吸急促、喉咙痛、持续咳嗽和嗅觉丧失)和 2) 多系统不适,包括持续发烧和胃肠症状 [ 20 ]。Survivor Corps 报告显示,26.5% 的 Long COVID 患者出现疼痛症状 [27-PP45] [ 29 ]。在长期 COVID 患者中,一些症状在急性症状出现后 3-4 周首次报告 [ 20 ]。

极度疲劳是一个常见问题,一项研究表明,在 SARS-CoV-2 感染后 10周的随访中;超过 50% 的人感到疲劳。疲劳的发展、COVID-19 严重程度和炎症标志物水平之间没有关联。女性和抑郁/焦虑的诊断在疲劳患者中更常见 [ 30 ]。感染 EB 病毒、埃博拉病毒、流感、SARS和 MERS 等病毒的人通常会出现病毒后疲劳。在没有任何其他原因的情况下,如果疲劳持续 6 个月或更长时间,则称为慢性疲劳综合症。从 2003 年的 SARS 中康复的患者中,高达 40% 患有慢性疲劳。存在慢性氧化和亚硝化应激、低度炎症和热休克蛋白生成受损是肌肉疲劳的拟议机制。极度疲劳不仅对患者而且对医疗保健提供者都是一个挑战,因为没有客观的方法可以确定地诊断它。在这种情况下,医患关系中的信任可能会中断 [ 31 ]。

SARS-CoV-2 感染可导致各种肺部并发症,如慢性咳嗽、纤维化肺病(COVID 后纤维化或 ARDS 后纤维化)、支气管扩张和肺血管疾病[ 32 ]。慢性呼吸急促可能是残余肺部受累的结果,众所周知,肺部受累会随着时间缓慢清除。不幸的是,许多无症状的 COVD-19 患者有明显的肺部受累,如CT 扫描所示。COVID-19 可能导致肺纤维化,从而导致持续呼吸困难和需要补充氧气。

COVID 19患者的常见心脏问题包括心率和血压对活动的不稳定反应、心肌炎和心包炎、微血管损伤导致的心肌血流储备受损、心肌梗塞、心力衰竭、危及生命的心律失常和心源性猝死。冠状动脉瘤、主动脉瘤、加速动脉粥样硬化、静脉和动脉血栓栓塞性疾病,包括危及生命的肺栓塞也可能发生 [ 33]. 其中一些可能在急性疾病康复后表现为长期 COVID。

CSF 中 SARS-CoV-2 的存在表明其具有神经侵袭性特征,并且可能会破坏从 COVID-19 康复的患者的微观结构和功能性大脑完整性 [ 34、35 ] 。头痛、震颤、注意力不集中;认知迟钝(“脑雾”),周围神经功能障碍;焦虑、抑郁和创伤后应激障碍等心理健康问题在长期 COVID 患者中很常见。英国的一项研究记录了 COVID-19 的神经精神表现。中风和精神状态改变是这一组中最常见的。由脑病或脑炎和原发性精神病诊断引起的多种精神症状在年轻患者中很常见 [ 36]. 在因 COVID 相关ARDS而接受俯卧位通气的患者中发现了获得性局灶性或多灶性周围神经损伤(PNI) [ 37 ]。任何原因导致的危重疾病和长时间机械通气都可能导致 ICU 获得性虚弱、功能失调、肌病、神经病和精神错乱。

COVID 后炎症会导致各种症状。必须将炎症性关节痛与类风湿性关节炎和系统性红斑狼疮等其他类似病症区分开来[ 38 ]。SARS-CoV-2 的严重感染可导致针对多种自身抗原的自身反应[ 39 ]。COVID-19 相关凝血病(CAC) 可导致动脉和静脉血栓形成[ 40 ]。

1.7 长 COVID 患者的处理方法

详细的病史和临床检查有助于对近期感染 SARS-CoV-2 的人进行诊断。对于有症状提示长 COVID 且既往没有 SARS-CoV-2 感染证据的患者,抗体阳性有助于确诊。然而,众所周知,抗体水平会随着时间的推移而下降。因此,血清学检测呈阴性并不能排除过去曾感染过 SARS-CoV-2。在这种情况下,长 COVID 的诊断可能具有挑战性。Raveendran 的长 COVID-19 诊断标准有助于将长 COVID-19 综合征分类为确诊、可能、可能或可疑 [ 12 ]。大多数患有长期 COVID 的人不需要进行广泛的评估。可以根据症状进行调查。

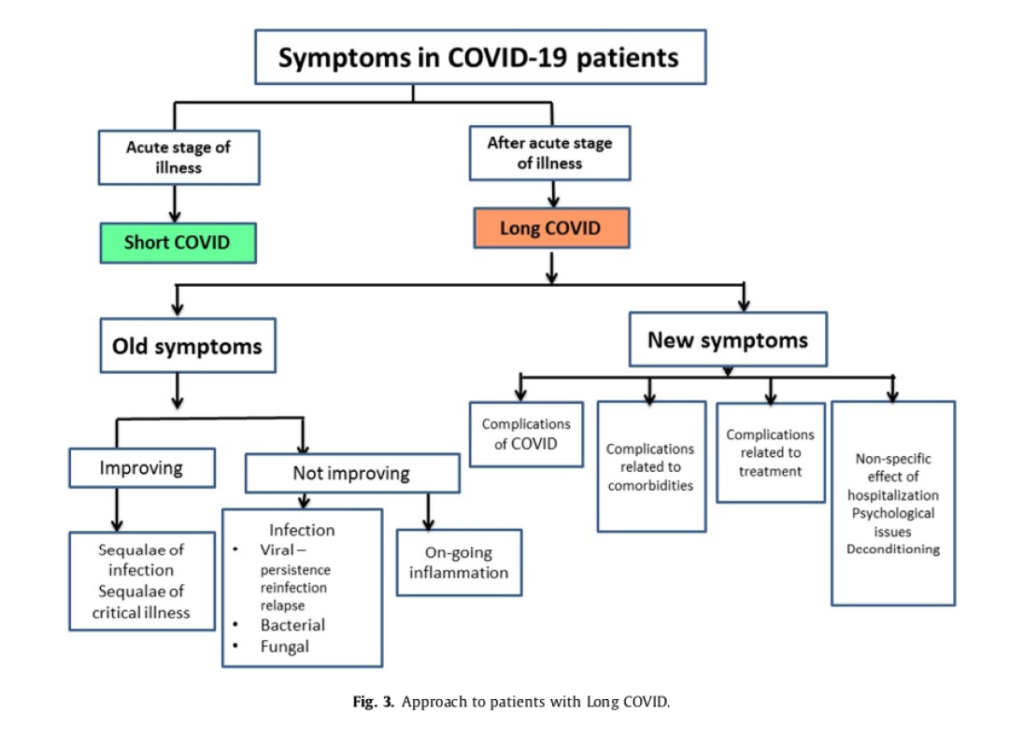

对长 COVID 患者的临床评估始于记录现有问题——其改善或恶化,以及记录新问题(如果有)(图3)。

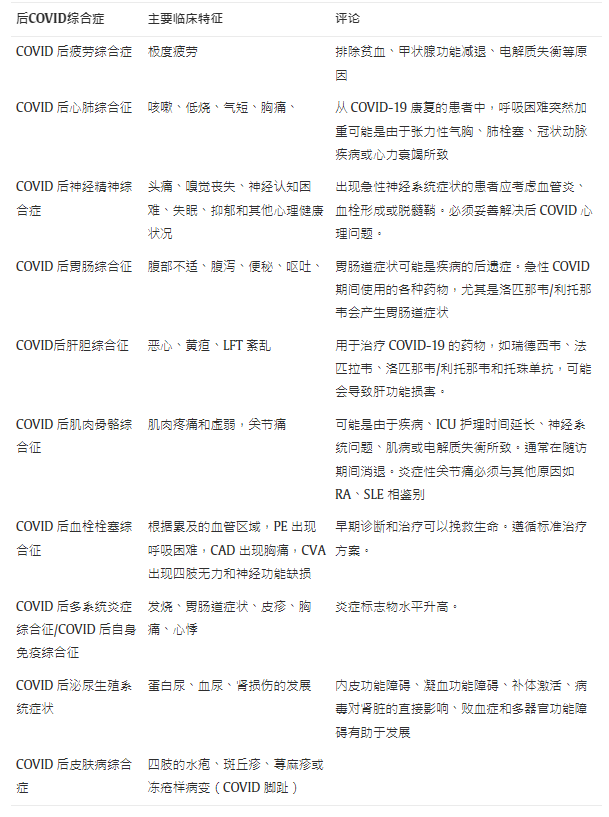

长COVID 可根据主要残留症状分为不同类别,如 COVID 后心肺综合征、COVID 后疲劳综合征和 COVID 后神经精神综合征[ 13、41、42 ]。(见表 1 )。根据所涉及的器官系统对症状进行分类将有助于确定病因。例如,对于呼吸困难的人,评估主要集中在心脏和呼吸系统受累上。严重疲劳需要排除常见原因,如贫血、高血糖、电解质失衡和甲状腺功能减退症,取决于临床情况。从 COVID-19 恢复后出现的任何新症状都应得到妥善处理,以排除气胸、肺栓塞、冠状动脉疾病和中风等危及生命的并发症(见表1)。

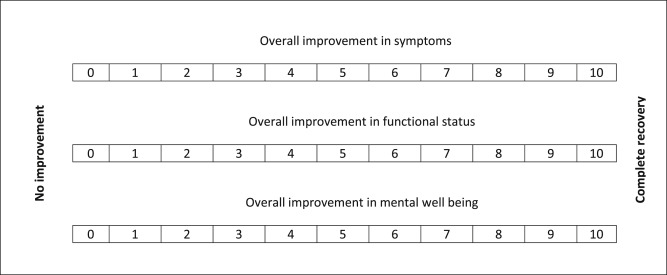

在每次访问期间,可以使用 0-10 的分数来评估症状的总体改善,其中 0 表示没有改善,10 表示完全恢复。对于有多种症状的患者,可以使用相似的评分来记录每种症状。整体功能状态改善和心理健康的整体改善也可以用 0-10 分来表示(见表2)。新症状的出现也可以通过 0-10 分来评估,前缀为“N”表示出现新症状。询问患者在 SARS-CoV-2 感染前的健康和功能状态有助于了解长期的影响冠状病毒。

1.8 长 COVID 患者的管理

长 COVID 患者的治疗需要采用多学科方法,包括评估、对症治疗、潜在问题的治疗、物理治疗、职业治疗和心理支持 [ 11 ]。咳嗽、疼痛、肌痛等轻微症状可以使用扑热息痛、止咳药和口服抗生素(如果怀疑继发性细菌感染)对症治疗。症状背后的病因(如果有),如肺栓塞、脑血管意外、冠状动脉疾病,必须按照标准方案进行治疗。胸部理疗和神经康复对于患有肺部和神经肌肉后遗症的患者很重要。由于它是一种新疾病,因此有关长期影响和治疗方案的知识仍在不断发展。感染 SARS-CoV-2 后,人们可能会出现糖尿病、高血压和心血管疾病等潜在合并症的恶化,需要优化治疗。

理想的随访频率和持续时间也没有明确定义。对于 COVID-19间质性肺炎患者,在最初的 12 个月内,建议与医疗保健专业人员进行 7 次互动(4 次面对面),以及 4 次 HRCT、4 次 6MWT、4 次血液检查(包括血细胞计数和代谢组)和2 SARS-CoV-2-IgG 测试 [ 43]. 根据我们的经验,大多数有轻中度症状的人和症状有所改善的人都可以通过在线或电话咨询进行跟进,减少面对面的互动。那些症状严重且进行性恶化的人需要经常亲自复查。应建议那些出现症状急性恶化或新症状急性发作的人立即报告急诊室。随访频率必须根据患者的临床情况进行个体化。

SARS-CoV-2 感染者症状的长期持续存在具有重大的社会和经济影响。随着疾病的继续传播,在不久的将来可能会有更多的人需要医疗保健支持,这可能会使医疗保健系统负担过重。关于长期 COVID-19 管理的明确指南将有助于消除医疗保健提供者之间的困惑。对 COVID 康复患者的长期随访将为“长期 COVID”及其管理带来更多启示 [ 44 ]。

2 . 结论

从 COVID-19(统称为 Long COVID)中恢复过来的人持续存在各种症状是世界范围内的一个主要健康问题。这可能是由于各种机制造成的,例如重症监护后综合症、病毒后疲劳综合症、永久性器官损伤或其他。适当的临床评估将有助于确定病因,并定制治疗方案。由于这种疾病是新出现的,因此要了解真正的长期前景还为时过早。

Abstract

Background and aims

Long COVID is the collective term to denote persistence of symptoms in those who have recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

WE searched the pubmed and scopus databases for original articles and reviews. Based on the search result, in this review article we are analyzing various aspects of Long COVID.

Results

Fatigue, cough, chest tightness, breathlessness, palpitations, myalgia and difficulty to focus are symptoms reported in long COVID. It could be related to organ damage, post viral syndrome, post-critical care syndrome and others. Clinical evaluation should focus on identifying the pathophysiology, followed by appropriate remedial measures. In people with symptoms suggestive of long COVID but without known history of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, serology may help confirm the diagnosis.

Conclusions

This review will helps the clinicians to manage various aspects of Long COVID.

1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) is a major pandemic resulting in substantial mortality and morbidity worldwide. Of the individuals affected, about 80% had mild to moderate disease and among those with severe disease, 5% develop critical illness [1]. A few of those who recovered from COVID-19 develop persistent or new symptoms lasting weeks or months; this is called “long COVID”, “Long Haulers” or “Post COVID syndrome.”

1.1. Acute COVID

Those infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus commonly develop symptoms 4–5 days after exposure. Acute COVID symptoms include fever, throat pain, cough, muscle or body aches, loss of taste or smell and diarrhea. A study from England, Wales and Scotland identified three clusters of symptoms during acute illness [2]. They are.

- •

respiratory symptom cluster: with cough, sputum, shortness of breath, and fever;

- •

musculoskeletal symptom cluster: with myalgia, joint pain, headache, and fatigue

- •

enteric symptom cluster: with abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea

COVID Symptom Study group identified six clusters of symptoms [3]. They are:

- •

“Flu-like” with no fever—headache, loss of smell, muscle pains, cough, sore throat, chest pain, no fever

- •

“Flu-like” with fever—headache, loss of smell, cough, sore throat, hoarseness, fever, loss of appetite

- •

Gastrointestinal—headache, loss of smell, loss of appetite, diarrhea, sore throat, chest pain, no cough

- •

Severe level one, fatigue—headache, loss of smell, cough, fever, hoarseness, chest pain, fatigue

- •

Severe level two, confusion—headache, loss of smell, loss of appetite, cough, fever, hoarseness, sore throat, chest pain, fatigue, confusion, muscle pain

- •

Severe level three, abdominal and respiratory—headache, loss of smell, loss of appetite, cough, fever, hoarseness, sore throat, chest pain, fatigue, confusion, muscle pain, shortness of breath, diarrhea, abdominal pain

Recovery from mild SARS-CoV-2 infection commonly occurs within 7–10 days after the onset of symptoms in mild disease; it could take 3–6 weeks in severe/critical illness [4]. However, continued follow up of patients who recovered from COVID-19 showed that one or more symptoms persist in a substantial percentage of people, even weeks or months after COVID-19.

1.2. “Long COVID”

The term long COVID was first used by Perego in social media to denote persistence of symptoms weeks or months after initial SARS-CoV-2 infection and the term ‘long haulers’ was used by Watson and by Yong [[5], [6], [7]].

“Long COVID” is a term used to describe presence of various symptoms, even weeks or months after acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection irrespective of the viral status [8]. It is also called “post-COVID syndrome”. It can be continuous or relapsing and remitting in nature [9]. There can be the persistence of one or more symptoms of acute COVID, or appearance of new symptoms. Majority of people with post-COVID syndrome are PCR negative, indicating microbiological recovery. In other words, post COVID syndrome is the time lag between the microbiological recovery and clinical recovery [10]. Majority of those with long COVID show biochemical and radiological recovery. Depending upon the duration of symptoms, post COVID or Long COVID can be divided into two stages-post acute COVID where symptoms extend beyond 3 weeks, but less than 12 weeks, and chronic COVID where symptoms extend beyond 12 weeks [11]. (Fig. 1).

Thus, among people infected with SARS-CoV-2 the presence of one or more symptoms (continuous or relapsing and remitting; new or same symptoms of acute COVID) even after the expected period of clinical recovery, irrespective of the underlying mechanism, is defined as post COVID syndrome or Long COVID.

There are several challenges in the diagnosis of long COVID. The time taken for the clinical recovery varies depending upon the severity of illness; while associated complications make it difficult to define the cut-off time for the diagnosis. A significant proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals are asymptomatic, and many individuals would not have undergone any test to confirm SARS-CoV-2 infection. If these individuals develop multiple symptoms subsequently, making a diagnosis of long COVID without a preceding evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection is challenging. The testing policy varies in different countries and it is a common practice during a pandemic to diagnose clinically based on symptoms without any confirmatory tests. Therefore, persistence of symptoms in those who had never checked for COVID is a challenge [12]. Similarly, residual symptoms in those checked negative for COVID (false negative as testing may be done too early or too late in the disease course) may also add to diagnostic dilemma [13]. Antibody response to infection also varies and about 20% does not seroconvert. Antibody level may decrease over time challenging the retrospective diagnosis of recent SARS-CoV-2 infection [14,15].

1.3. “Long COVID”-real world scenario

A report from Italy found that 87% of people recovered and discharged from hospitals showed persistence of at least one symptom even at 60 days [16]. Of these 32% had one or two symptoms, where as 55% had three or more. Fever or features of acute illness was not seen in these patients. The commonly reported problems were fatigue (53.1%), worsened quality of life (44.1%), dyspnoea (43.4%), joint pain, (27.3%) and chest pain (21.7%). Cough, skin rashes, palpitations, headache, diarrhea, and ‘pins and needles’ sensation were the other symptoms reported. Patients also reported inability to do routine daily activities, in addition to mental health issues such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Another study found that COVID-19 patients discharged from hospital experience breathlessness and excessive fatigue even at 3 months [17].

The prevalence of residual symptoms is about 35% in patients treated for COVID-19 on outpatient basis, but around 87% among cohorts of hospitalized patients [16,18].

The percentage of people, who failed to return to their job at 14–21 days after becoming COVID positive, was 35% according to one survey [18]. It is more common in older age groups (26% in 18–34 years, 32% in 35–49 years and 47% in 50 years and above), and among those with co morbidities (28% with nil or one co-morbidity, 46% with two and 57% with three or more co morbidities). Obesity (BMI>30) and presence of psychiatric conditions (anxiety disorder, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, paranoia, obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia) are associated with greater than two-fold odds of not returning to job by 14–21 days after a positive result [18]. Fever and chills present in the acute stage of infection resolved in 97% and 96% of individuals respectively. But cough, fatigue and shortness of breath did not resolve in 43%, 35% and 29% of patients during interview. Loss of taste and loss of smell took longer duration for resolution (8 days). As per a recent meta analysis the 5 most common manifestations of Long COVID-19 were fatigue (58%), headache (44%), attention disorder (27%), hair loss (25%), dyspnea (24%) [19].

Among patients admitted to critical care unit who were on ventilator for a prolonged time, residual symptoms are common. However, COVID patients who had mild disease also report not regaining their pre-COVID health status, effectively questioning the terminology of “mild” disease.

1.4. Risk factors for long COVID

Follow up of patients recovered from COVID identified a few factors which are commonly associated with development of long COVID. The risk of long COVID is twice common in women compared to men [9]. Increasing age is also a risk factor and it is found that patients with long COVID are around four years older than those without [9]. Presence of more than 5 symptoms in the acute stage of illness is associated with increased risk of developing long COVID [20]. Symptoms most commonly associated with long COVID include fatigue, headache, dyspnea, hoarse voice and myalgia [20]. Presence of co morbidities also increases the risk of developing post COVID syndrome. Even those with mild symptoms at initial presentation were noted to develop long COVID.

1.5. Pathophysiology of “Long COVID”

The exact mechanism behind the persistence of symptoms has to be identified. Reason for the persistence of symptoms can be the sequelae of organ damage, varying extent of injury (organ damage) and varying time required for the recovery of each organ system, persistence of chronic inflammation (convalescent phase) or immune response/auto antibody generation, rare persistence of virus in the body, nonspecific effect of hospitalization, sequelae of critical illness, post-intensive care syndrome, complications related to corona infection or complications related to co morbidities or adverse effects of medications used [21,22].(Fig. 2) Persistence of infection can be due to persistent viremia in people with altered immunity, re-infection or relapse [[23], [24], [25]]. Deconditioning, psychological issues like post-traumatic stress also contribute to symptoms [[26], [27], [28]]. The social and financial impact of COVID-19 also contributes to post COVID issues including psychological issues. Differentiating residual symptoms from re-infection is important in the public health perspective. Persistently elevated inflammatory markers point towards chronic persistence of inflammation. It is helpful to remember that in any patient, multiple mechanisms may contribute to long COVID symptoms.

1.6. Common symptoms in “Long COVID”

Common symptoms in people with “Long COVID” are profound fatigue, breathlessness, cough, chest pain, palpitations, headache, joint pain, myalgia and weakness, insomnia, pins and needles, diarrhea, rash or hair loss, impaired balance and gait, neurocognitive issues including memory and concentration problems and worsened quality of life. In people with “Long COVID” one or more symptoms may be present.

Researchers identified two main patterns of symptoms in people with long COVID: they are 1) fatigue, headache and upper respiratory complaints (shortness of breath, sore throat, persistent cough and loss of smell) and 2) multi-system complaints including ongoing fever and gastroenterological symptoms [20]. Survivor Corps report shows that 26.5% of people with Long COVID experienced painful symptoms [27-PP45] [29]. In patients with long COVID some of the symptoms are first reported 3–4 weeks after the onset of acute symptoms [20].

Profound fatigue is a common problem and one study showed that at 10 weeks of follow up after SARS-CoV-2 infection; more than 50% of people were suffering from fatigue. There was no association between development of fatigue, COVID-19 severity and level of inflammatory markers. Female sex and diagnosis of depression/anxiety is more common in those with fatigue [30]. Post viral fatigues are commonly reported in people with viral infections like EBV, Ebola, influenza, SARS and MERS. In the absence of any other reason, if fatigue persists for 6 months or longer it is called chronic fatigue syndrome. Up to 40% of patients who recovered from SARS of 2003 have chronic fatigue. The presence of chronic oxidative and nitrosative stress, low-grade inflammation and impaired heat shock protein production were among the proposed mechanisms for muscle fatigue. Profound fatigue is a challenge not only to the patient but also the healthcare provider, as there are no objective methods to diagnose it with certainty. Disruption of trust in the doctor-patient relationship can occur in such settings [31].

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 can leads to various pulmonary complications like chronic cough, fibrotic lung disease (post-COVID fibrosis or post-ARDS fibrosis), bronchiectasis, and pulmonary vascular disease [32]. Chronic shortness of breath could be the result of residual pulmonary involvement, which is known to clear slowly with time. Unfortunately, many asymptomatic patients with COVD-19 have significant lung involvement, as shown on CT scans. COVID-19 may lead to pulmonary fibrosis, which can result in persistence of dyspnea and need for supplementary oxygen.

Common cardiac issues in patients from COVID 19 include labile heart rate and blood pressure responses to activity, myocarditis and pericarditis, impaired myocardial flow reserve from micro vascular injury, myocardial infarction, cardiac failure, life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Coronary artery aneurysm, aortic aneurysm, accelerated atherosclerosis, venous and arterial thromboembolic disease including life threatening pulmonary embolism can also occur [33]. Several of these may manifest as Long-COVID after recovery from acute illness.

Presence of SARS-CoV-2 in CSF shows its neuro-invasive features and there is possible disruption to micro-structural and functional brain integrity in patients recovered from COVID-19 [34,35]. Headache, tremor, problem with attention and concentration; cognitive blunting (“brain fog”), dysfunction in the peripheral nerves; and mental health problems like anxiety, depression and PTSD are common in people with long COVID. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19 have been documented in a British study. Stroke and altered mental status were the commonest among this group. Multiple psychiatric symptoms stemming from encephalopathy or encephalitis and primary psychiatric diagnoses, were noted commonly in young patients [36]. Acquired focal or multifocal peripheral nerve injury (PNI) was noticed in those who received prone ventilation for COVID related ARDS [37]. Critical illness and prolonged mechanical ventilation due to any cause can results in ICU-acquired weakness, deconditioning, myopathies, neuropathies and delirium.

Post COVID inflammation can result in various symptoms. Inflammatory arthralgia has to be differentiated from other similar conditions like Rheumatoid arthritis and SLE [38]. Severe infection with SARS-CoV-2 can results in autoreactivity against a variety of self-antigens [39]. COVID-19 associated coagulopathy (CAC) can results in both arterial and venous thrombosis [40].

1.7. Approach to patients with long COVID

Detailed history and clinical examination help with the diagnosis in people with recent SARS-CoV-2 infection. In patients with symptoms suggestive of long COVID, without previous evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, demonstration of antibody positivity helps to confirm the diagnosis. However, antibody levels are known to drop with time; therefore a negative serology test does not rule out a past SARS-CoV-2 infection. In such scenario diagnosis of long COVID can be challenging. Raveendran’s criteria for the diagnosis of long COVID-19, helps to categorise as confirmed, probable, possible or doubtful long COVID-19 syndrome [12]. Majority of the people with long COVID does not require extensive evaluation. Investigations may be directed by symptoms.

Clinical evaluation of patients presenting with long COVID starts with documentation of the existing problem-its improvement or deterioration, and also documentation of new problems, if any (Fig. 3).

Long COVID can be divided into different categories depending upon the predominant residual symptoms as post COVID cardio-respiratory syndrome, post COVID fatigue syndrome and post COVID neuro-psychiatric syndrome [13,41,42]. (See Table 1). Categorization of symptoms according to the organ system involved will help to identify the etiology. For example, in people with breathlessness, evaluation mainly focuses on cardiac and respiratory system involvement. Severe fatigue necessitates ruling out common causes like anemia, hyperglycemia, electrolyte imbalance and hypothyroidism, depending upon the clinical scenario. Any new onset symptoms after recovery from COVID-19 should be properly addressed to rule out life threatening complications such as pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, coronary artery disease and stroke (see Table 1).

During each visit, the overall improvement in symptoms can be assessed by using score of 0–10, where 0 represents no improvement, and 10 represents complete recovery. In patients with multiple symptoms, each symptom can be documented using a similar score. Overall functional status improvement and overall improvement in mental wellbeing can also be represented by a score of 0–10 (see Table 2). Appearance of new symptoms can also be assessed by a score of 0–10, with a prefix of “N” to indicate new symptoms. Enquiring about the patient’s health and functional status before SARS-CoV-2 infection helps to understand the impact of long COVID.

1.8. Management of patients with long COVID

Treatment of people with long COVID requires a multi-disciplinary approach including evaluation, symptomatic treatment, treatment of underlying problems, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and psychological support [11]. Minor symptoms like cough, pain, myalgia can be treated symptomatically with paracetamol, cough suppressants and oral antibiotics (if secondary bacterial infection is suspected). Etiology behind the symptoms, if any, like pulmonary embolism, cerebrovascular accident, coronary artery disease, has to be treated as per the standard protocol. Chest physiotherapy and neuro rehabilitation is important in patients with pulmonary and neuromuscular sequelae. Since it is a new disease, the knowledge regarding long term effects and treatment options is still evolving. Worsening of underlying co-morbidities like diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular illness could occur in people after SARS-CoV-2 infection, requiring optimization of treatment.

The ideal frequency and duration of follow up is also not clearly defined. In people with COVID-19 interstitial pneumonia, in the first 12 months, 7 interactions with healthcare professionals (4 face-to-face) are recommended, alongside 4 HRCTs, 4 6MWT, 4 blood tests (including blood count and metabolic panel) and 2 SARS-CoV-2-IgG tests [43]. In our experience, majority of people with mild-moderate symptoms and those who show improvement in symptoms can be followed up with online or telephonic consultation, with fewer face-to-face interactions. Those with severe symptoms and progressive worsening need frequent in-person review. Those developing acute worsening of symptoms or acute onset of new symptoms should be advised to report the emergency department immediately. Frequency of follow up has to be individualized according to patient’s clinical profile.

Chronic persistence of symptoms in people with SARS-CoV-2 infection has significant social and economic impact. As the disease continues to spread, more people may need health care support in the near future, which could overburden the health care system. Clear guidelines regarding management of long COVID-19 will help clear the confusion among health care providers. Long term follow up of COVID recovered patients will throw more light into “long COVID” and its management [44].

2. Conclusion

Persistence of various symptoms in people who recovered from COVID-19 (collectively called Long COVID) is a major health issue worldwide. It could be due to various mechanisms such as post-intensive care syndrome, post-viral fatigue syndrome, permanent organ damage or others. Proper clinical evaluation will help identify the etiology, and to customize treatment. As the disease is new, it is too early to know the true long-term outlook.